No one gets married looking into the future and seeing divorce. Ending a marriage is more often than not an earth-shattering event in a person’s life. Here is attorney James Sexton’s advice regarding how couples can avoid finding themselves in a lawyer’s office.

To read the complete article click here

“We’re raised to look at marriage as this milestone and we keep signing up for it,” says James Sexton. “There are very few behaviors that end so badly so frequently that we would just sign up for it with such reckless abandon!”

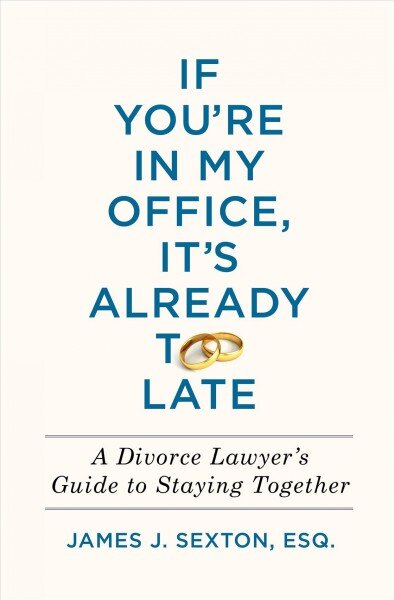

Sexton has personally witnessed the demise of more than a thousand marriages — but that’s right folks, you guessed it — he still believes in love. Not only that, but his career helping people out of marriages inspired him to write a how-to book on staying together: If You’re In My Office, It’s Already Too Late.

So what does a divorce lawyer, who’s seen the worst kind of behaviors in human relationships, know about how to do it right? “Over these years, I’ve seen so much of what people do wrong that you could probably reverse-engineer that into what they might have done differently,” he says.

Interview Highlights

On never hiring attractive babysitters

On reinventing yourself with your partner, as opposed to after divorce

Do it in a way that’s constructive, as opposed to destructive. And do it sooner rather than later. People come to me, they’ve already lost the plot. They had a story they were trying to write together, everyone who gets married wants it to last. No one can pretend — in this curated world we live in where everyone puts everything on social media and it’s always the best version of what they’re doing, divorce is refreshing in the sense that you can’t pretend you meant to be in my office. No one meant to be in my office.

On preserving a union

The core answer isn’t that sexy. What it really is is, just stay connected with your spouse. Communicate with your spouse, remember that you fell in love with a person who had unique traits, and there were little things you just did for each other. You were cheerleaders for each other at some point. But when you’re married it’s very very easy to just not even see the person anymore, much less cheer for them. You know, whoever discovered water, it wasn’t a fish. When you’re in something, you don’t see it so clearly anymore. So I encourage people to step back from their marriage, to take a very clear inventory of it, and to really pay attention. And the other thing I think is equally important is being painfully honest with your spouse about what’s going on in your heart, and what’s going on in your head.

On advice for his clients

I just tell people that they should just try to see the best version of themselves in whatever choice they make. It’s really hard to stay together, and it’s really hard to split up. And what I really try to tell people in the book, and certainly in the conclusion to the book, is whatever path you choose, try to remember that marriage was appealing to you and to your spouse because you both had a very human need for connection and for love, and for someone who was cheering for you in a world that feels very antagonistic sometimes. And my advice to everyone is, stay out of my office if you can, but if you need to come to my office, I hope I see the most compassionate, thoughtful version of you, I hope I see a version of you that focuses on your kids, and that focuses on ending your relationship with dignity.

This story was produced for radio by Sophia Boyd and Barrie Hardymon, and adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer.